Who Watches the Watchers?

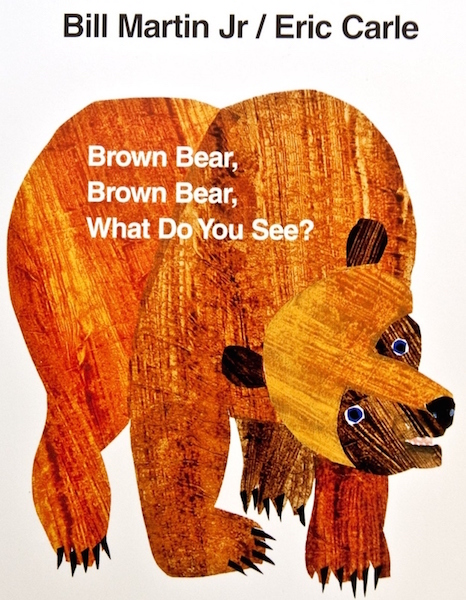

When Emma was seven months old, I wrote a 900-word review for a 200-word children's book. It was the 1,132nd five-star review of Brown Bear, Brown Bear, What Do You See? (hardcover edition).

It has since been marked as "helpful" by over 400 Amazon customers and enjoyed and a brief stint as the top review for this particular publication, which probably means that this Amazon review which I wrote while high on sleep deprivation is the most read thing I've ever written.

I'm reposting below, but you should read it in it's original and true form.

Who Watches the Watchers?

This has been the book of choice for my seven month old daughter’s bed time. We heard that it’s better to read the same book over and over to young kids so that they become familiar with matching up the words and the sounds.

I know it seems like a simple book, but there’s a lot more depth to be uncovered on repeated readings, as I’ve had the luxury of experiencing every night, and multiple times during the day, for the last three months.

It opens with a simple question: “Brown Bear, Brown Bear, what do you see?” And if you were to judge this book by its cover, you might assume the bear to be the protagonist of the story. But as it unfolds, we are…

** SPOILERS BELOW **

… taken through a tour of the real and familiar (brown bears, red birds) along with the fantastically surreal (blue horses, purple cats). And despite the cartoonish illustrations and unassuming prose, we come to find that this is a world of paranoia and domestic surveillance. A world where neighbor spies upon neighbor.

“Brown bear, brown bear, what do you see?”

“I see a red bird looking at me.”

“Red bird, red bird, what do you see?”

“I see a yellow duck looking at me.”

The book begins with a lie. When the red bird is asked, “What do you see?”, the correct answer is “a brown bear.” But she does not admit that she is spying on the brown bear, only complains that the yellow duck is spying on her.

As the cardboard pages turn, we learn that all characters are being watched: from the strong (the bear), to the useful (blue horse), to the outcast (black sheep). We learn that all characters know that they are being watched (presumably, knowing that they are being watched keeps them in line). And we learn that all the characters, except for the bear, are watching one of their peers. It’s interesting that this society’s only celebrity – the titular bear – is the only character to be watched by his peers without the power to watch back. I assume this is Martin’s commentary on the impotence of fame.

As the camera pulls back, we learn that each animal is merely a minor player with myopic vision. In its dramatic, Usual Suspects-esque conclusion, we learn that we are not in a forest or frolicking in the outdoors. An authority figure is introduced:

“Goldfish, goldfish, what do you see?”

“I see a teacher looking at me.”

With the introduction of this (white) teacher we realize that these characters who seemed to be free, roaming in their natural habitat, are actually prisoners trapped in the hardbound confines of this book. And yet, even the teacher’s vision is limited, for she too is trapped.

“Teacher, teacher, what do you see?”

“I see children looking at me.”

The children are vastly more powerful and knowledgeable than any other character. For it is only they – the readers themselves – who see all of the characters.

“Children, children, what do you see?”

“We see a brown bear,

a red bird,

a yellow duck,

a blue horse,

a green frog,

a purple cat,

a white dog,

a black sheep,

a goldfish,

and a teacher LOOKING AT US.

That’s what we see.”

It is those three words – “looking at us” – that are most chilling.

If the animals were looking at the children this whole time, why don’t they say so? When the bear was asked what he saw, he mentioned only the bird. When the bird was asked what she saw, she mentioned only the duck. Every single character in the book is looking at the children and yet every single one refuses to admit that they see them. It’s only the authority figure who has the courage to acknowledge their presence.

How tight must the children’s tyrannical grip be to force an entire population into unified submissive silence? The children have complete control, for they not only know everything about the world the characters inhabit, but they also possess the power to destroy that world, as many of this book’s youngest readers undoubtedly have.

It is the proverbial bear who is not to be poked. But through the bear’s opening omission we learn that even he is too scared of the children to publicly acknowledge his awareness of their existence. The true revelation to this book’s opening question is not that the Brown Bear sees the Red Bird. It’s that he also sees the omniscient, omnipotent children, but is too terrified to say so.

But the children know that he knows.

I don’t believe the rumors that this book originated as recruitment propaganda by US intelligence agencies to entice young children to join an elite, “all-seeing” organization that exerts complete control over the rest of the population, including its powerless authority figures.

Instead, I like to believe that Martin wrote this book, just one year after regular US troops were deployed to Vietnam, as a subversive allegory daring to ask the question “Who watches the watchers?” A question more important today than ever before.

A+++. Would read again.

And again.

And again.

And again.

And oh dear God make it stop.